It took 18 more years and seven tries for my grandfather to make it to the top. For him, reaching the summit was always a simple, honest, honorable quest. It was something he did not for medals, money or fame but for himself. Getting there was enough.

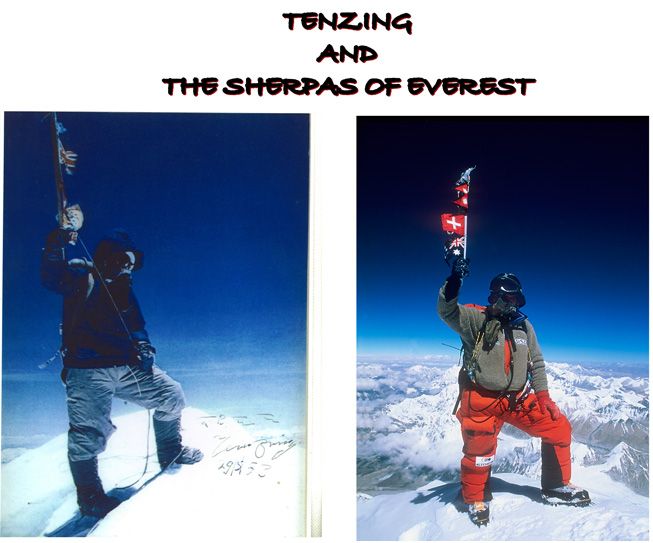

Tenzing Norgay and the Sherpas of Everest.

The world outside the Himalaya discovered'' Mount Everest in the late 19th century. Since then, foreigners have sought to conquer, market and control the mountain. Though Sherpas and their Tibetan kin had known Everest - or Chomolungma - for centuries, not one of them wanted to climb it until my grandfather, Tenzing Norgay, came along. He made it to the summit, with Sir Edmund Hillary, 50 years ago today - and life for Sherpas has never been the same.

My grandfather's dream to climb Everest was unusual for someone of his culture and traditional outlook. In fact, Sherpas once believed that the great summits were the dwelling places of Buddhist spirits and as such must not be violated. But even as a young lad in Nepal, my grandfather wondered about Everest and whether it would be possible to make it to the top. His family made good-humored fun of his talk. In 1935, however, they were compelled to take him seriously. That year, he joined the Everest expedition of Eric Shipton, a British climber, which made it to the north east ridge but a far shot from the top.

My grandfather's dream to climb Everest was unusual for someone of his culture and traditional outlook. In fact, Sherpas once believed that the great summits were the dwelling places of Buddhist spirits and as such must not be violated. But even as a young lad in Nepal, my grandfather wondered about Everest and whether it would be possible to make it to the top. His family made good-humored fun of his talk. In 1935, however, they were compelled to take him seriously. That year, he joined the Everest expedition of Eric Shipton, a British climber, which made it to the north east ridge but a far shot from the top.

Of his experience standing atop Everest he wrote: From his autobiography “Tiger of the Snows” (ghost wrotten by James Ramsay Ullman: ``My mountain did not seem to me a lifeless thing of rock and ice, but warm and friendly and living. She was a mother hen and the other mountains were chicks under her wings.''

In the 50 years since my grandfather and Sir Edmund Hillary made their climb, Everest mountaineering has become a popular adventure sport - about 10,000 people have tried to reach the top - and a booming business. This has been a mixed blessing for us Sherpas. On the one hand, it has helped usher in a better standard of living than we could have ever imagined. Tourism is a lucrative industry - a climb can cost as much as $65,000, and for each group of seven climbers, Nepal charges $70,000 in royalties. And the attention of Everest has led many, including Sir Edmund, to invest in education and health care for my people. Infant mortality rates have decreased (only six of 14 children in my grandfather's family survived infancy), while literacy rates have climbed.

Tenzing Norgay memorial stupa

The stupa was built in honour of Tenzing Norgay and the Sherpas of Everest. Situated on the way from Namche to Tengboche, the stupa was inaugurated on May, 9, 2003, by Tashi Tenzing Sherpa, grandson of Tenzing Norgay and two-time Everest summiteer.

The influx of Western tourists to Everest has introduced Sherpas to a new kind of lifestyle, leading many to crave an easier, more cosmopolitan existence in the cities and abroad. Few people, especially working-age men, option to stay in the mountains. Indeed, I do not wish to make my livelihood plowing high-altitude fields of barley. Many villages are now home only to the frail and elderly, and the few relatives who remain to take care of them.

But life for Sherpas has become increasingly complicated. Many of our young people are understandably tired of the hardship - the freezing winters and scarce food - and are no longer satisfied grazing yaks or growing potatoes in difficult terrain at high altitudes.

For the able-bodied Sherpas who do remain behind, however, Everest has provided a lucrative source of income.

Most expeditions include three or four climbing Sherpas (about one per climber) and between 20 and 30 Sherpas to carry loads to the base camps. A Sherpa guide can earn about $2,000 during a two-month climbing season, about eight times the average per capita income in Nepal.

But this work is also very dangerous: at least 175 climbers have been killed trying to reach the top of Everest. Many join expeditions without life insurance, which is expensive and difficult to get, knowing that if they do not return there will be little for those left behind beyond the good will of their community. Most Sherpa guides, however, are philosophical about the risks.

When asked how much longer he would climb on Everest with big expeditions, Ang Dorje, a Sherpa guide, did a quick calculation on his fingers and said, ``Four more times,'' the amount it would require to build his home and educate his children.

I don't think my grandfather would be disheartened by the path we Sherpas have followed. He used to say that he climbed so that we (his offspring) would not have to.

Indeed, many in my family have gone on to become doctors and businessmen, but some of us have also climbed Everest. 6 family members have climbed Everest since Tenzing. I have been lucky. I have managed to hold on to both worlds. I have reached the summit of Everest twice but have never had to carry 35 kg porter loads as my grandfather and so many other Sherpas did. In fact, in 1993, I was the first ethnic Sherpa to lead an international climbing team (an expedition in which Western climbers carried their own loads).

I am happy that my grandfather's climb paved the way for modernization among the Sherpas. My people now have greater opportunities to learn to read and write, have a voice in the affairs of their region and build a brighter future for themselves.

I only hope that their increasing wisdom and empowerment can spread to the mountaineering world, where they are still so often viewed as mere load-carriers and often nameless catalysts to Western success.

Learn to Surf with Us